Preface

- This article contains some spoilers for “The French Powder Mystery”, “The Tragedy of X”, “The Greek Coffin Mystery”, “The Chinese Orange Mystery,” providing slight hints (without revealing the culprits or methods, so it doesn’t hinder the initial reading) for “The Siamese Twin Mystery,” “Halfway House,” “The Devil to Pay,” “Ten Days of Wonder,” “Cat of Many Tails,” “The Glass Village,” and “Wings in the Dark.” It also includes spoilers for the original anime episodes of “Detective Conan” in the section about “The Shifting Mystery of Beika City.”

- This article is intended for readers who have read several books by Ellery Queen, at the very least, those books that have been spoiled. Additionally, there may be paragraphs that provide hints about the plots of other works, so it is recommended that you have a certain understanding of the author’s style in different periods. The characteristics of the four periods are not reiterated here. However, it is worth noting that in the author’s opinion, if we ignore Queen’s period of inactivity in writing novels (1958-1963), combining the third and fourth periods into one period makes the characteristics more prominent.

- In this article, “Ellery” refers to the detective character, while “Queen” refers to the author. The usage of “Ellery Queen” depends on the context.

- Some subjective opinions may be expressed in parts of this article. If there are omissions or errors, please do not hesitate to point them out.

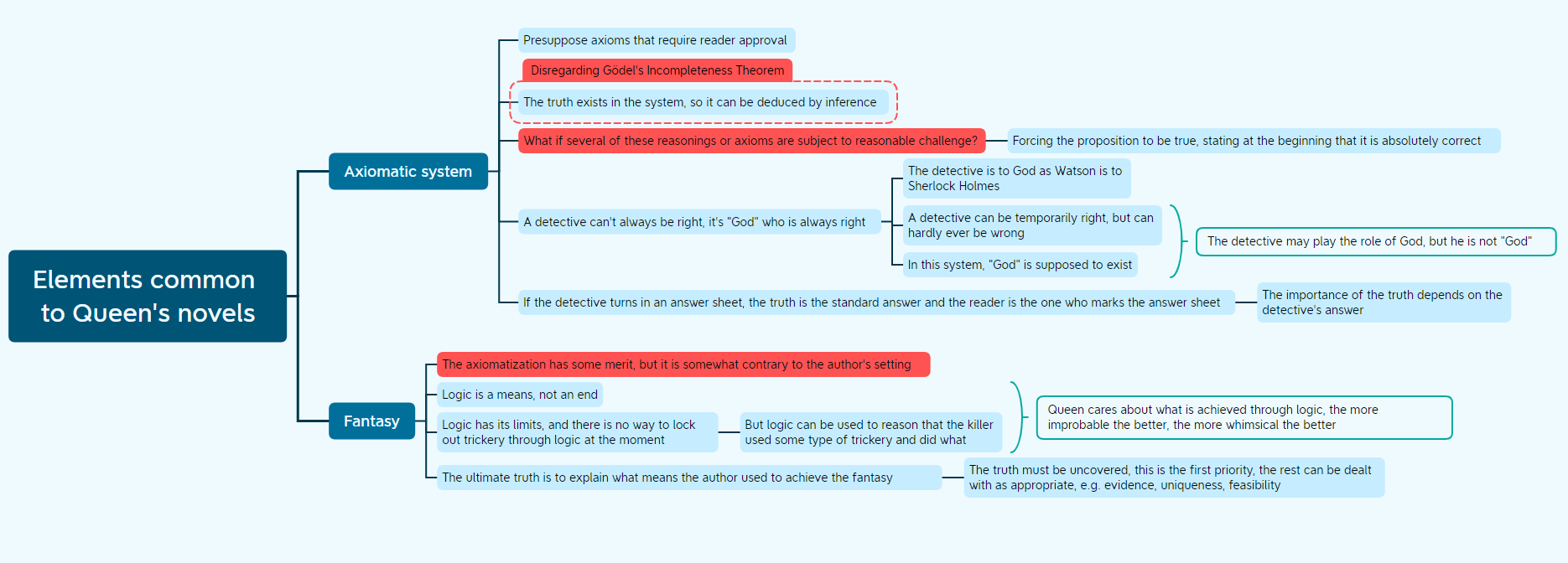

- The theme of this article is to compare the axiomatic method with Ellery Queen’s design of detective reasoning, and explore their creative perspectives. It then attempts to standardize Queen’s reasoning process. Afterwards, it reverses the approach and analyzes how Queen makes the reasoning process legitimate without relying on axioms. This analysis extends to the later issues of Queen and his detective novels.

- Although this article uses some mathematical concepts, it is designed to be understandable even for readers who are not familiar with the subject. If there are any unclear points, please let me know.

Preparatory: Spectrum Analysis

The axiomatic method is an important approach in mathematics, with its main essence being to derive as many propositions as possible from a minimal set of axioms and several primitive concepts.

In other words, as long as you accept these few axioms as correct, you can deduce numerous valid conclusions based on them. Euclid is a notable figure in axiomatic methods, as he developed “Elements of Geometry” by using 23 definitions, five postulates, and five axioms, from which he deduced 465 propositions using logical deduction rules.

Applying the Axiomatic Method to Detective Novels – Allow me to provide a personal definition of “axiomatization in detective novels.” It refers to the content that the author presents to the readers as something “we both should agree on” or “a common understanding” (such as the fact that humans have two hands).

Regarding the part of the content that “we both should agree on,” Carr made a lot of effort. Please refer to the first chapter of “The Three Coffins”:

“Therefore it must be stated that Mr Stuart Mills at Professor Grimaud’s house was not lying, was not omitting or adding anything, but telling the whole business exactly as he saw it in every case. Also it must be stated that the three independent witnesses of Cagliostro Street (Messrs Short and Blackwin, and Police–constable Withers) were telling the exact truth.”

In this context, the “axioms” refer to the statement that the testimony of certain individuals is completely trustworthy.

In “The Reader is Warned,” Carr goes even further and provides three footnotes with the warning “The reader is warned.”:

- In looking over these notes of what I said, I think it only fair to add that Constable was not killed by any mechanical device which operated in the absence of the guilty person. The presence of the guilty person was necessary to make the method succeed. The reader is warned.

- In looking over my notes of this case, even now I am struck with the number of suggestions that were made about various people working as somebody else’s accomplice. It will, perhaps, allow better concentration if I state here that the murderer in this case worked entirely alone, and had no confederate who either knew the murderer’s plan or rendered material assistance in any way. The reader is warned.

- A very just remark, I can see now. The motive for murder, though fully indicated in the text, is not obvious on the surface; and it involves indeed, a legal point. Anyone interested in solving the problem may be advised to look carefully below the surface. The reader is warned.

Here, there are three “axioms”: the culprit must be present at the scene of the crime, the culprit acted alone and no one knew their plan, and the motive of the culprit has been mentioned earlier in the text. If Carr did not state these axioms, readers could potentially be led astray and reach conclusions that are logically sound but different from the solution in the novel.

Establishing axioms serves to ensure fairness and strive to create a logical closure in the reasoning process (i.e., the most reasonable solution without other “illogical” possibilities). However, it should be noted that this is only a guess, and the conclusions reached are still not absolute.

In essence, axioms can also be seen as a form of compromise because the author cannot guarantee their truth through other means, so they have to forcefully declare them as true. In other words, if the author does not make a declaration about a certain point of doubt (assuming it is not deducible), it cannot be judged as true or false.

With this definition of axioms, readers can easily associate it with Ellery Queen’s “Challenge to the Reader,” which ensures that all the clues are provided through the challenge, thereby explaining why “The Siamese Twins Mystery” did not have a “Challenge to the Reader.” The reason is the same as what Kaoru Kitamura mentioned in “The Japanese Coin Mystery”: because if you put the challenge in, the reader would immediately see the errors in the previous reasoning. And furthermore:

“In ‘The Siamese Twins Mystery,’ the decisive blow that identifies the culprit is actually based on a certain action of the culprit at that time. Of course, there is also a set of logical clues to explain it, but ultimately, it is concluded through a non-logical form. So, it’s not that there is no ‘Challenge to the Reader.’ ‘The Siamese Twins Mystery’ is a story that couldn’t have included a ‘Challenge to the Reader’ from the beginning.”

(This paragraph is quoted from “The Complete Guide to Ellery Queen” by Yusan Iiki, in the section about “The Siamese Twins Mystery.”)

In the eighth chapter, fourth section of “Murder for Pleasure,” Howard Haycraft wrote, “When asked about the key to the acclaim and success of Carr’s novels, the author modestly said it was the technique of ‘absolutely logical’ fair deduction.” (This quote is from the translation in “The Ellery Queen Centenary Collection.”) Indeed, in order to achieve this “absolutely logical” fair deduction, choices must be made regarding the “Challenge to the Reader.”

If we consider the “Challenge to the Reader” as an axiom (where all the clues are given), then the previous reasoning would be illogical, and readers would anticipate a twist later on. Therefore, Carr had to abandon the “Challenge to the Reader” to increase suspense because he didn’t want it to be “illogical.”

Of course, you may argue that the “Challenge to the Reader” could be included before the false solution, but then it would be similar to “The Greek Coffin Mystery.” For the creator, this might be an act that diminishes the credibility of “Challenge to the Reader.”

At this point, you might have objections to the aforementioned “axiom theory”: you speculate a reasonable explanation based on the fact that the “Challenge to the Reader” does not appear in “The Siamese Twins Mystery” and forcefully claim that Carr’s logical flow uses axiomatic methods. It may seem far-fetched and forced.

The reason I feel and believe that Carr employs axiomatic methods is based on rereading “The Spanish Cape Mystery.”

Chapter 10:

“Hmm. Now, that’s damned interesting. Good work, Mr. Queen. Only why didn’t you let me in on it?”

“You don’t know this young man,” remarked Judge Macklin dryly. “He’s the loneliest wolf in captivity. I daresay he kept his mouth shut because he hadn’t worked the thing out by his blasted logic. It wasn’t a mathematical ‘certainty’; merely a probability.”

“How well you read my motives,” chuckled Ellery. “Something like that, Inspector. What do you think of my little tale?”

Chapter 15:

“Because,” sighed Ellery, “my work is done with symbols, Mr. Godfrey, not with human beings. And I owe a duty to Inspector Moley, who has been kind enough to let me run wild in his bailiwick. I believe, when all the facts are known, that the murderer of Marco stands an excellent chance of gaining the sympathy of a jury. This was a deliberate crime, but it was a crime which—in a sense, as you imply—had to be done. I choose to close my mind to the human elements and treat it as a problem in mathematics. The fate of the murderer I leave to those who decide such things.”

If there were Ellery Queen scholars to tally the frequency of the word “logic” in Ellery Queen’s works, I believe the number would certainly exceed a hundred.

What kind of logic is it? Generally, it relies on deductive reasoning, with major and minor premises leading to a conclusion. It’s not about guessing—

“A Queen,” said Ellery severely,” never guesses.”

(The Egyptian Cross Mystery, Chapter 30).

Some readers might raise a counterexample: in The Tragedy of X, Drury Lane directly conjectures that the ticket swapping occurred before or after the murder and uses it as a basis for further reasoning.

However, this doesn’t prove anything. Lane’s assertion is based on the fact that this conclusion can explain all the facts. He then proceeds to reason further, considering where this conclusion leads him, and subsequently matches the current clues and facts to verify its reliability. He does not directly propose a possibility as a usable conclusion.

Returning to the previous discussion, Ellery Queen’s character is such that he only reveals the “possible solution” when it becomes the “actual truth.” So how does one bring the solution to fruition? It relies on “symbolic deduction” and a “mathematical approach.”

Delving further into this “mathematical approach,” it brings to mind the aforementioned method of axiomatization.

If we consider the novel as a graph, with many points on it, at the beginning of the novel, we already have some axioms. Based on the clues and facts provided by the plot, we obtain several starting points. We then use deductive reasoning to derive extended conclusions (represented on the graph as edges connecting points) and treat these conclusions as new correct “axioms” to deduce the solution (completing the entire graph with a path from the starting point to the endpoint).

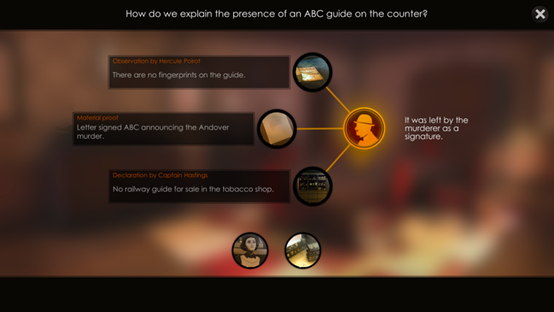

Taking the reasoning in the game “The ABC Murder” as an example:

The game is a remake of “The ABC Murders” and employs the packaging method shown in the diagram to present logical reasoning. It connects multiple points (conclusions) to derive a single point (solution).

If the logical reasoning in detective novels were attempted using this form, it would likely be easier to adapt them into games.

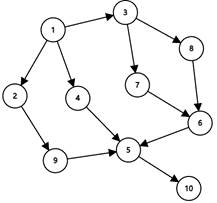

Here’s another example:

In order to derive the truth 10 from the initial axiom 1, the following process occurs: Based on reasoning, conclusions 2, 3, and 4 are derived from axiom 1. Conclusion 2 leads to conclusion 9, while conclusion 3 leads to conclusions 7 and 8. Conclusions 7 and 8 together lead to conclusion 6. Then, using conclusions 4, 6, and 9, conclusion 5 is derived. Finally, based on conclusion 5, the truth 10 is deduced.

This demonstrates a similar axiomatization method. However, Hercule Poirot’s logical reasoning is not solely based on deductive reasoning; he also employs methods of induction and organizing conclusions. He eliminates conclusions that contradict the facts and retains only the ones that align with the available clues.

If there are any logical gaps in the reasoning, the author introduces a new axiom to correct them. In summary, this approach requires readers to accept the axioms set by the author as absolute authority.

Constructing a diagram or schematic based on the case, the evidence, and the inferences surrounding the case can be considered a method of case analysis. One such method is the Wigmore chart developed by American jurist John H. Wigmore and later optimized by American jurist Terence Anderson and British jurist William Twining. For more details, refer to “Evidence Analysis.”

The origin of axiomatization can be traced back to the fact that all reasoning is based on a certain foundation of reality, as mentioned at the beginning of the text, which is the “commonly accepted understanding.” However, this consensus is often vague. “Consensus” may not be knowledge that everyone knows, and what A considers as a consensus may not be the same for B. If A bases their reasoning on this consensus, it will certainly be challenged by B. For example, in an exaggerated scenario, if A claims, “The deceased died three days ago, but their will was legally verified to have been written today, which indicates that the will is forged.” This reasoning is based on the consensus that “dead people cannot write a will.” However, if someone argues that the deceased has come back to life, faked their death, or possessed another person’s body to complete the will, the reasoning falls apart because there is a problem with the consensus. Therefore, we can only say that readers should not doubt everything.

Should the author ask the readers, “Do you agree with this understanding here?” or “Do you accept this common knowledge there?” Unfortunately, due to the limitations of the novel genre, this is impossible to achieve.

However, there are times when the author indeed needs to seek the readers’ agreement because the consensus assumed by the author may not be as reliable as imagined. In such cases, the concept of “strongly assumed axioms” comes into play.

But then new questions arise. Following the reasoning of Hilbert’s 23 questions, the second question can be posed as follows: How can we prove that the axiom system is consistent, meaning that through a finite number of logical operations, we can never derive contradictory results from these axioms themselves? Therefore, if we are to believe in this method, we must subsequently prove that contradictions will not occur.

At this point, you may recall the discussion of axiomatization in the section “The Continuum Hypothesis” in the novel “Literary Girls vs Mathematical Girls” by Lu Qiucha. He argues that even with the addition of axioms, the gaps cannot be filled but rather new gaps will emerge. The supporting evidence is Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, which states that any consistent axiom system that includes elementary arithmetic statements will inevitably have an undecidable proposition that cannot be determined true or false using that set of axioms. However, whether this theorem can be directly applied to detective fiction reasoning remains to be considered, as it imposes stringent conditions. It should not be directly analogized to detective fiction or even directly applied as a theorem. Take the example of a locked-room mystery; it is evident that exhaustive enumeration of methods under the current limiting conditions cannot be achieved, therefore, such a system of thought must not be complete.

However, if we don’t strictly reference mathematical theorems but instead compare and construct the axiom system of detective fiction, it could be worth attempting.

The passage also states: “After adding such ‘axioms,’ masterpieces like ‘The Greek Coffin Mystery’ or ‘The Siamese Twin Mystery’ would never have been created…”

But if we analyze it this way, that adding axioms would cause problems, then even without adding axioms, “The Siamese Twin Mystery” itself would have issues—where is the starting line for fair competition between readers and detectives? Has the author directly erased it?

Based on this, I believe that the reason why gaps arise is because it is difficult to determine the truth or falsity of a certain clue.

If we think in this way (believing that adding axioms is useless), it will create a dilemma: Either the author intentionally deceives the audience, or they will tirelessly go back and forth in proving the truth or falsity of a particular clue, ultimately achieving nothing.

Taking “The French Powder Mystery” as an example, the clue that seals the victory is fingerprint powder:

“From the moment that I was certain of the nature of the powder, the veils dissipated before my eyes and I sensed the truth. We thought at first, ladies and gentlemen,” he continued, “that the use of fingerprint powder by the criminal indicated a very superior sort of murderer—a super-criminal, in fact. One who would use the implements of the police’s own trade —it was a natural thought . . . .

“But”—and the word lashed into them with deadly emphasis—”there was another inference to be drawn—an inference which in a fell swoop eliminated all suspects but one . . . .” His eyes flashed fire; the hoarseness disappeared from his voice. He leaned forward carefully, over the desk with its litter of clues, holding them with the magnetism of his personality. “All suspects—but one . . . ” he repeated slowly.

Ellery himself admits that he locked onto the killer based on the reasoning that “the person who used fingerprint powder must have an official background.” However, upon closer inspection, this reasoning appears to have flaws—why couldn’t someone have framed him? Perhaps the real killer stumbled upon the knowledge of fingerprint powder and used it to devise a plan of framing.

If Ellery wants to eliminate this possibility, what should he do? Firstly, he cannot exclude the existing clues because if he could, he would certainly explain them instead of relying solely on the statement “the person must have an official background,” which seems reasonable but cannot be considered evidence. Next, he would have to provide additional clues to prove that no one other than the killer would use fingerprint powder.

But then the new question arises: Could these additional clues also be part of the killer’s design? Thus, a chain of suspicion is formed, and the question of which additional clues are true and which are fabricated becomes endless.

Don’t laugh, such problems need to be constantly considered in later works by Ellery Queen.

In conclusion, this kind of thinking casts a shadow over everything. The verdict is: From the moment you start doubting the axiomatic system, the whole situation becomes irreparable. It seems that it can be endlessly doubted.

The current solution is quite simple, as mentioned earlier, the approach taken by Carr: breaking the fourth wall and telling the readers directly what is believable and what must be true. Personally, I believe this method is effective.

At first glance, the dark clouds seem to disperse, but the subsequent problem becomes more serious: If the axiomatic system is established, with fixed axioms and the assistance of certain clues, people can mechanically follow a reasoning method to deduce all sub-conclusions, leading ultimately to the identification of the killer. Then, what is the use of a detective? The entire process can be handed over to a machine, where the killer inputs the case, and artificial intelligence outputs the solution.

In “Ten Days’ Wonder,” Ellery Queen fails. In Francis M. Nevins’ book “Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection,” it is mentioned that Ellery is in a confrontation with “God” (this “God” has a slightly different meaning than the one mentioned later, which would be a spoiler. Readers who haven’t read the work can understand this “God” as an immensely powerful and unbeatable entity). However, Ellery manages to recover and, at the beginning of “Cat of Many Tails,” he believes he can solve the case. So he started again, but in the end he realized that, despite his great ability, he would still experience one failure after another:

I’ve had a long and honorable career indulging my paranoia. Talk about delusions of grandeur! I’ve given pronunciamentos on law to lawyers, on chemistry to chemists, on ballistics to ballistics experts, on fingerprints to men who’ve made the study of fingerprints their lifework. I’ve issued my imperial decrees on criminal investigation methods to police officers with thirty years’ training, delivered definitive psychiatric analyses for the benefit of qualified psychiatrists. I’ve made Napoleon look like a men’s room attendant. And all the while I’ve been running amok among the innocent like Gabriel on a bender.”

“This in itself,” came the voice, “this that you say now is a delusion.”

…

“In that sense—yes, Mr. Queen, you failed.” The old man leaned forward suddenly and he took one of Ellery’s hands in his own. And at his touch Ellery knew that he had come to the end of a road which he would never again have to traverse. “You have failed before, you will fail again. This is the nature and the role of man.

“The work you have chosen to do is a sublimation, of great social value.

“You must continue…”

The key point lies in this sentence: “You have failed before, you will fail again. This is the nature and the role of man.” This sentence can be said to have killed the past Ellery Queen.

After countless battles, mortals finally discover that even if they give their all, there will always be something they cannot see, something beyond their power. Although Ellery might eventually arrive at the truth, the predetermined truth given by “God,” the process is like a student checking answers on an exam paper. It only tells you whether your answer is right or wrong, without revealing how to correct it. All you need to do is reproduce the answer, and that’s it.

When the truth is revealed, everyone is happy, but it is a world where only the detective is wounded.

From this perspective, Ellery Queen may be one of the earliest detective novelists to discuss the end of the detective’s journey. As a detective, his growth process is long and meticulous. The renowned detective thinks it’s a smooth ascent, unaware that in the end, there is an unfathomable abyss separating him from the heavens. The higher he climbs, the higher the cliff.

However, humans fail, fail again, until they reach the truth, while a machine can succeed in one attempt.

If there truly exists an unbiased, Gödel-incompleteness-proof artificial intelligence (of course, at present it doesn’t exist; the artificial intelligence trained on correct data faces the same problem of “how to solve false solutions” as humans do), but I believe there is a high possibility of its emergence in the future, just like the possibility of extraterrestrial life in the universe, then we should call it “God” (here, emphasizing omniscience and omnipotence).

Hence, the last sentence is profound: “There is one God; and there is none other but he.”

The detective who acts as a divine agent is insignificant in the face of divine reasoning. He doesn’t know where to go, and the author doesn’t know where he is going either.

But in front of us, it is precisely because they persevere through repeated failures in the quest for the truth that the story evolves into a legend.

Thus, the entire discussion on the axiomatic system is complete.

Deus Ex Machina

Next, let’s further analyze “The Tragedy of X” as an example. The reason for selecting this work is simple: its framework is the clearest. Through the concise and clear reasoning process in the book, we can see how the protagonist, Drury Lane, progresses from the starting point to the endpoint.

The main reasoning process consists of three stages:

Reasoning Method:

- Based on all the clues and evidence at the crime scene, determine what the culprit could and could not have done.

- Further, if the culprit did something they shouldn’t have been able to do, deduce the method they used (eliminate possibilities from simple to difficult and arrive – at the most likely option).

- The conclusions obtained from stages 1 and 2 serve as new clues.

Repeat the above steps:

- Utilize the new conclusions as starting points and continue the reasoning process.

- Based on the new clues, determine what the culprit could and could not have done.

- Deduce the method used if the culprit did something they shouldn’t have been able to do.

- Repeat this process until all necessary clues are obtained.

For example, let’s consider the reasoning process related to gloves as a starting point:

“And everyone was searched thoroughly?”

“Yes,” said the Inspector in a scathing tone.

“Believe me, Inspector, casting aspersions on the efficiency of your auxiliaries is furthest from my thought . . . . As a confirmation, sir, once again: Nothing unusual was found on the persons of the occupants of the car, or in the car itself, or in the rooms of the barn after everyone left— anywhere?”

“I think I brought that out, Mr. Lane,” replied Thumm coldly.

“Nevertheless—nothing that would seem out of place, considering the weather, the season, the type of persons involved?”

“I don’t get you.”

“For example—you found no topcoats, evening clothes, gloves— things like that.”

“Oh! Well, one man had a raincoat, but I examined it myself and it was okay as I told you. Otherwise, no articles of the sort you mentioned. I can absolutely vouch for it.”

(In this passage, Lane is processing all the clues and evidence he currently knows.)

Train of thought:

- Based on the major premise (axiom): The culprit used a weapon for the crime; minor premise (evidence): The weapon had a cork filled with needles; conclusion: The culprit picked up the cork, so they must have used the cork. Contradiction: The culprit should not have been able to pick up the cork.

- Only one possibility remains: The culprit used some kind of tool to protect their hands. Considering the previous context and ruling out a handkerchief, the conclusion is that the culprit used gloves.

- The fact that there were gloves on the train becomes a new conclusion and clue.

- Repeat step 1: There should have been gloves on the train, but now there aren’t any. New conclusion: Someone disposed of the gloves.

- Repeat step 2: Rule out all the people, and the ticket seller is the only one left. New conclusion: The ticket seller is involved and disposed of the gloves.

Reasoning based on gestures

Train of thought:

- Connect two stages of reasoning.

- In the first stage, deduce that the gestures were made before being shot (deductive reasoning: struggling after being shot is impossible).

- In the second stage, infer that the gestures are related to the murder (maximum likelihood: treat the highly probable event as the actual event). Dewitt’s gesture is difficult to make, and Dewitt had heard Lane talk about leaving a final message before dying. Therefore, the gesture is highly correlated with the murder.

- Contradiction: The gesture should have been made with the right hand, but it was made with the left hand (humans only have two hands). Therefore, it can be deduced that his right hand was busy during the incident.

- Contradiction: The train ticket was originally in the left breast pocket of the vest, but after the incident, it was found in the inner pocket of the coat. Therefore, it can be inferred that the train ticket was intentionally moved.

- Combining the above three points, it can be concluded that Dewitt held the train ticket in his right hand and made the gesture with his left hand before his death. This statement aligns with all the clues and inferences obtained so far.

- Furthermore, by excluding the people on the train, it can be determined that the culprit is the ticket seller.

Exclusion method:

- List all possible conclusions or approach exhaustive enumeration to cover the entire range.

- Use deductive reasoning to support or refute the possible conclusions:

Refutation: If proposition A can be deduced based on the existing clues, then the possible conclusion cannot include the negation of A. If it does, it is falsified.

Support: If the negation of the possible conclusion B contradicts the existing conclusions, then the possibility of B is credible.

e.g.

Is Wood the culprit or an accomplice?:

Approach:

- If Wood is the culprit, there are three possible scenarios:

- Wood is the culprit and there is an accomplice who assists in the crime, but in the end, this accomplice kills Wood.

- Wood acted alone without any accomplice, and he wanted to shift the blame onto an innocent third party but was killed by that person.

- Wood was killed for other reasons unrelated to the Longstreet case, which are currently unknown.

- Methods of refutation were applied to all three possibilities.

- Wood being an accomplice seems plausible (not using a supporting method, but this possibility appears self-consistent).

- At this point, there is a lack of evidence, and further investigation is required.

- Completion of the evidence, refuting the possibility of Wood being an accomplice, confirms the fourth possibility that Wood is the culprit, which is the only true solution.

Mr Lane’s reasoning is brilliant, but can we expect him to fail a few times as well?

Ellery Visits The Past

If you don’t agree with the axiomatization approach to explain why “The Siamese Twin Mystery” doesn’t have a challenge to the reader, you can refer to Yusan Iiki’s explanation in “The Theory of Ellery Queen.” According to Iiki, the challenge posed by Queen in this case is not “guessing the culprit” but rather “guessing Ellery’s reasoning.” In “The Siamese Twin Mystery,” it is impossible for readers to guess Ellery’s reasoning. (This paragraph is not quoted from the original text but is from the section on “The Siamese Twin Mystery” in “The Complete Guide to Ellery Queen” by Yusan Iiki.)

To refute the claim that Ellery Queen used axiomatization, it’s quite simple. Just ask, “Why is Ellery, who is supposed to be skilled in logic, not good at mathematics?” If we accept the previous axiomatization argument, it becomes difficult to answer this question. It creates a dilemma: If Ellery indeed used axiomatization, his logical deductions should be excellent, or else he wouldn’t arrive at the correct conclusions. Similarly, since mathematics often involves reasoning, he should excel in that as well. However, the reality is the opposite. If we argue that Ellery’s mathematics skills are not good, which is why he frequently stumbles due to imperfect logic in later stories, it undermines the correctness of his earlier logical deductions.

Even introducing Julian Symons’ hypothesis (in “The Great Detectives”) that “The Door Between” should be considered the last book of the first period of Queen’s career, suggesting that the Ellery Queen who appears later is a different character from the first period’s Ellery, does not help. In the first period’s “The Spanish Cape Mystery,” Ellery already admits to not being good at mathematics (although he mentions solving puzzles using mathematical methods):

“I can’t complain. In my blood, no doubt. There’s a chemical something inside me that shoots to the boiling-point at the least approach of criminality. Nothing Freudian about it; it’s merely the mathematician in me. And I failed in geometry in high school! Can’t understand it, because I love discordant and isolated twos and twos, especially when they’re expressed in terms of violence. Marco represents one of the factors in the equation. That man positively fascinates me.”

The contradictory setup of Ellery’s character traits, such as his proficiency in logic but not in mathematics, was established during the first period when the Ellery Queen brothers relied on logic for their victories. If we introduce axiomatization theory, it would only add to the inconsistency. Therefore, it should be understood that the mathematical methods used by Ellery cannot be generalized to the entire field of mathematics.

Thus, we can conclude that it is absurd to explain Ellery’s reasoning using the axiomatization method employed in mathematics.

Of course, such assertions may not fully consider the potential shifts in the author’s thinking that may have occurred over decades of writing.

To analyze Ellery Queen’s logical reasoning, it is necessary to consider both the perspective of the author and the readers.

Ellery Queen’s works are not suitable for categorization as tricks. In “The Chinese Orange Mystery,” for example, according to John Dickson Carr, the trick can be summed up as “locking with a dead man” (from the 17th chapter of “The Three Coffins: The Locked Room Lecture” on creating the illusion of a locked door from inside the room). Yusan Iiki, suggests that using ice to lock the door is also a valid solution from the perspective of guessing the murderer’s method (discussed in his article “The Manipulation of Queen: An Examination of the ‘Manipulation’ in Queen’s Works” published in the EQFC journal).

The original intention behind Queen’s creation of this work was the “end-justifies-the-means” principle, where the goal is to deduce the solution. Therefore, any locked room method is acceptable as long as it is reasonable.

Indeed, there are many possible solutions to the locked room mystery, but Ellery Queen’s focus was not on finding all possible methods. He only wanted to find one feasible method to complete a logical chain:

The killer used a certain method to create the “locked room” -> People in the office couldn’t enter this “locked room” -> The killer is not among the people in the office.

Therefore, Ellery’s reasoning goes: The “locked room” was achieved through a certain method -> The killer must be among the people in the office.

Based on the analysis above, my conclusion is that Ellery Queen cannot definitively determine the method used to lock the room through logic alone.

If the persuasiveness of this argument based solely on this work may seem insufficient, let’s consider “The Devil To Pay” as an example. When Ellery deduces the method used by the killer to murder Solomon Spaeth, what conclusion does he arrive at? That the killer used a certain weapon, but why can it only be that weapon? Based on certain evidence. However, this logical chain is very weak because it is too easy to manipulate that evidence. In reality, what Ellery wants to prove is not that specific conclusion, but rather the inference that the killer must possess a certain skill. To establish the existence of this skill, the plot must include clues pointing to this particular expertise left by the killer at the crime scene.

In this sense, I would describe this kind of reasoning as “close enough.” It means that there is not a unique method of committing the crime, and the conclusions reached through deduction may not perfectly align with what actually happened, but the person involved certainly engaged in similar behavior.

Similar to the difference between player thinking and planning thinking in game design, this type of reasoning is not so much detective thinking as it is author thinking. Specifically, the author designs the logical chain with the ultimate goal of pointing towards a certain conclusion, while the detective considers the logical chain to see what conclusions can be derived from it.

Furthermore, from the author’s perspective, the deductive reasoning used in “The French Powder Mystery,” “The Tragedy of Z,” and “Halfway House” is more likely designed based on the desired conclusion. It is evident that the most crucial constraint in “The French Powder Mystery” and “Halfway House” is the one that directly points to the killer and no one else. Other constraints do not have the same effectiveness or directness.

If we accept the above explanation, we can provide a set of answers to the question “Readers’ and authors’ preferences for works differ greatly”:

- The author is very proud of the work because it explains/reveals a surprising fact through deduction.

- The author is not satisfied with the work because it didn’t achieve the desired effect.

- Readers love the work because the process of deduction is thrilling or the plot twists are clever.

- Readers are not satisfied with the work because the novel’s process is too dry and the revelation doesn’t align well with it (either a plot-based or a puzzle-based solution, even though the author may think the solution is hanging in the air).

In Ellery Queen’s fifty-year writing career, their favorite works are not easily changed. In “In the Queens’ Parlor,” Dannay expressed his love for “The Chinese Orange Mystery.” When asked about his top 3 works in 1977, he listed “The Chinese Orange Mystery,” “Calamity Town,” and “Halfway House.” This means “The Chinese Orange Mystery” was Dannay’s favorite work (the evidence for the top 3 list is taken from the chapter on “The Chinese Orange Mystery” in “The Complete Guide to Ellery Queen”). In Kaoru Kitamura’s “The Japanese Coin Mystery,” we see Dannay’s personal top 6 selections, and the other three books are “The Cat of Many Tails,” “The Glass Village,” and “And on the Eighth Day.”

If we use the above answers, we can explain some of the preferences. The reason for liking “The Chinese Orange Mystery” is that the inverted room, a fantastical puzzle, is made plausible through the explanatory technique. The reason for liking “And on the Eighth Day” is that the final “collapse” is achieved through the layout of the Valley of Quenan. As for “Cat of Many Tails,” let’s consider the following passage:

“Let’s talk about this question. Ellery arrives at his conclusions without relying on the usual clues and the typical Queenian reasoning. I think I made it clear to you—during our telephone conversation and in my letters—that I deliberately avoided the Queenian methods in ‘The Chinese Orange Mystery’ and even the methods in ‘Calamity Town.’ I told you repeatedly that I’m not writing a detective mystery… What I gave Ellery was—I repeat, deliberately—a kind of mental magic. He weaves seemingly reasonable conclusions, even if they are purely conjectures, but they are highly believable… Don’t you think that most readers—vast majority—find Ellery’s conclusions not only seemingly reasonable but also very convincing? If so (and I believe they do), then this trick is accomplished—without relying on actual evidence as in typical detective novels… What I’m trying to do is to move away from Queen’s old methods of proving X and only X can be the culprit… Because the new method is not as irrefutable as mathematical formulas or experimental discoveries, what did I make Ellery do? Ask questions thousands of miles away! I repeat—ask questions!”

“Calamity Town” is a work that Ellery Queen himself is quite proud of, and this may be because it represents a turning point for him. In the Nationality Series, the story always starts with a murder or a corpse, followed by a relentless investigation and interviews. However, “Calamity Town” breaks away from this pattern. It arranges for Ellery to enter a strange town, become acquainted with the townspeople, understand the conflicts among them, and the murder slowly unfolds during this process until it finally occurs. This kind of narrative pattern is not uncommon in other mystery novels, but it was indeed a significant change for Ellery Queen as he delves into the plot as it unfolds. So, what method does Ellery use for his deductions in this book?

In a manner similar to Hercule Poirot in “Five Little Pigs,” Ellery relies heavily on psychological evidence: a general conclusion combined with the behavior and state of the individuals involved to support that conclusion. From his works prior to the Third Period, it is evident that the proportion of psychological evidence is much lower compared to physical evidence. However, since “Calamity Town,” the proportion of psychological evidence has significantly increased.

In “Cat of Many Tails,” Ellery still needs to prove that X is the culprit but cannot use the form of “because of the existence of conclusions one, two, three, and four, only X is the culprit.” The new writing approach is to present a false solution based purely on conjecture, without any evidence, but to make the readers convinced, and then fail, leading to the true solution and revealing a surprising murderer and motive.

This concept is actually reflected in Chapter 26 of “There Was an Old Woman”:

“You’ll have to dig up the proof yourself, Dad,” said Ellery at last, uncoiling his long legs. “All I can do is supply the truth.”

“Yeah. The trouble is,” said Sergeant Velie, dryly, “they ought to fix up a new set o’ laws for you, Maestro. The kind of case you make out—it puts the finger on murderers but it don’t put ’em where they can get a hot foot in the seat.”

For this task, Ellery Queen believed that they both did an excellent job, and Lee thought that “Cat of Many Tails” would become a monumental work. They expressed through Seligmann’s words,

“Do you know, Herr Queen, this is extraordinary. I can only sit and admire… For you have arrived, by an uncharted route, at the true destination.”

In “The Essence of Detective Fiction” by Dannay, there is a concise statement that summarizes their creative philosophy:

The essence of detective fiction is to turn the impossible into possible.

So, if they achieve this goal, they would obtain the greatest satisfaction.

Taking into account the content discussed in this section, from the perspective of the authors, the logical problems in detective fiction are important because they care about the effects that logical reasoning can produce, rather than the perfection of logic itself.

Once we reach this conclusion, the importance of the axiomatic system diminishes. As mentioned above, logical reasoning is merely a creative tool and not the absolute core of detective fiction.

This leads to a more radical assertion: although logical reasoning has always been one of Ellery Queen’s two labels (in my opinion, the other being later-stage Ellery Queen problems), they may not perceive it that way. They might not consider logic as their distinctive feature. Instead, they might believe that logic alone was sufficient in the early stages to explore the vast realm of detective fiction. The categorization of Ellery Queen as representing logic flow or the Queenian style by later generations is merely their wishful thinking.

In “Blood Letters,” Dannay tells Lee the following:

In this field, no one—absolutely no one—can surpass what Ellery Queen is famous for. Who else can write a work like “The Origin of Evil”? If you agree with this point, then you must ask yourself: shouldn’t Ellery Queen continue to produce works that embody the distinctive features that Ellery Queen fans eagerly anticipate? Fantasy, the fantasy of the Queenian style, is not an ordinary commodity. By continuing in this manner, offering something unique to us, providing the unmistakable Ellery Queen characteristics, how much value does that hold?

Not everything can be achieved through fantasy, but logic happens to be a means to fulfill fantasy, although it is not the only means. However, does this contradict Howard Haycraft’s quote? Objectively speaking, Ellery Queen believed that “the technique of absolutely fair reasoning based on absolute logic” was the key to the acclaim and success of detective novels in the 1930s. But does that represent Ellery Queen’s creative purpose? Clearly, reasons and objectives cannot be directly equated. Even in the early period, many Queenian fantasies were present: why would a vanished hat become the key to a case? How could an exhibition display case become a hiding place for a body? How could a murder occur in a hospital? Three linked murders taking place on three different modes of transportation? Characters in the story repeatedly drawing incorrect conclusions? How would a person tainted by evil unleash such dreadful crimes? How could a decapitated body trigger a hunt spanning thousands of miles? How could a detective identify the sole murderer among twenty-seven suspects? How could one swiftly eliminate twenty thousand suspects and find a missing gun? How could a 300-year-old Shakespearean mystery be solved by a Shakespearean actor three centuries later? How would a crime unfold during a mountain fire? How could a completely inverted world be restored? Why would a murder require the victim to be completely naked? Among the thirteen full-length novels, there were not only logical deductions but also various imaginative ideas. We should not overlook these.

Therefore, I believe the perspective of “achieving fantasy through logical reasoning” holds true for the early period. Moving on to the “potential changes in the author’s thoughts over decades of creation” mentioned earlier, it is mentioned in both “The Tragedy of Errors” and “Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection.” Forty years after the publication of “The Roman Hat Mystery,” Dannay saw the synopsis of the book in “Royal Bloodline” by Nieves and felt a sense of strangeness, not believing that he had written that book.

Therefore, I should clarify that this ongoing fantasy lasted for forty years. In the subsequent period, we have examples such as the disappearing house in “The Lamp of God,” the vanishing train in “The Siamese Twin Mystery,” the peculiar club in “The Last Man Club” the magical metaphor in “The Origin of Evil,” the twelve consecutive gifts in “The Finishing Stroke,” and the storm-tossed mansion constructed of brass in “The Brass House.” These examples are numerous.

“Ten Days’ Wonder” took Dannay ten years and many sleepless nights to create. However, during this process, he may have only conceived the final truth, while the answers to the series of questions that lead to the conclusion were not his doing. In “Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection,” there is a letter from Lee to Boucher which states:

“What was left to me …was to try to smother the enormous ridiculousness of it all under the cloak of sheer rhetoric….[E]very last morsel of psychological interpretation in the finish is my own;there was none in the original.The whole thread of the father-image and its ramifications I set into the fabric.Arousing, I might add, the most vehement response of all from Dan [i.e.Fred]….”

Clearly, even the explanation was not initially designed for this “vast absurdity.” Therefore, I believe that Queenian fantasy permeates the entire creative process.

Regarding the perspective on fantasy, I consulted Professor Yusan Iiki, who believes that fantasy is defined by its inability to be rationally explained. For example, no adult would consider a mirage a fantasy because everyone knows it is a scientific phenomenon caused by the refraction of light. Ellery Queen’s deductions disrupt fantasy. Thus, through reasoning, fantasy ceases to be fantasy. That is why his deductions are surprising.

I believe that someone who does not understand the principles of a mirage would be amazed the first time they see one, finding it dreamlike. Then, a detective-like character appears, explaining the phenomenon with optical principles and suddenly, they understand that there is an explanation for this fantasy. Explaining miracles does not destroy fantasy but rather makes people realize that fantasy can indeed occur.

Taken together, it could be said that Queen’s works are filled with fantasy, and this perspective is correct. Furthermore, Queen strives to explain/break fantasy, resulting in “unexpected deductions.” Personally, I think this “further step” is a bit presumptuous, as the “unexpected deductions theory” cannot explain the case of “And on the Eighth Day.”

Or perhaps you would argue that the transformation after the second period was only to cater to the demands of the market and magazines—yes, that is probably the main reason. However, sales and remuneration do not represent everything. Just consider how much remuneration a style of detective novel like “Ten Days’ Wonder” could earn at that time. In “The Complete Guide to Ellery Queen,” it is mentioned that Dannay stated in an interview that it took him ten years to complete the outline for this novel. The difficulty and time-consuming nature of the creation process cannot be explained solely by a transformation to cater to the market.

How I wish readers would not mistakenly think that Queen after the first period willingly succumbed to a decline and suffered from a depletion of creativity. Although the current promotional materials give that impression, one can only say that logic is both the cause of success and failure.

No Man is a Hero

From the discussion in Part 3, it can be seen that regarding the “late-period Queen” issue, Dannay himself has given a similar definition: “Ellery had no actual evidence, no tangible clues on which to reason. Ellery depended on ideas, on words, on intangibles. Ellery depended on his mind – not on the physical clues as he had before. He now depended on human thoughts, motives, actions, secrets.” Therefore, “he weaves seemingly reasonable conclusions, even if they are purely conjectures, but they are highly believable… Don’t you think that most readers—vast majority—find Ellery’s conclusions not only seemingly reasonable but also very convincing? If so (and I believe they do), then this trick is accomplished.”

But despite saying that, the much-criticized Knox problem in “The Greek Coffin Mystery” is derived from Ellery’s ideas: Knox manages to clear himself of suspicion by paying 1000 dollars, which seems logical. However, from the first failed solution in Chapter 15 to the discovery of the banknotes in the gold watch in Chapter 24, during this interval Knox would have had ample time to return the 1000 dollars, so the foundation of eliminating Knox as a suspect is not solid. Therefore, I think Dannay’s statement is not accurate, and even in early works, there are issues of hasty assumptions.

Even if we consider the principle of “letting the simpler explanation prevail”: if Knox were the culprit, keeping the banknotes to prove his innocence would require assuming corresponding risks, so he should have taken them back. The explanation is persuasive. However, if such an explanation had indeed been considered by the author, it should have been written down, but in reality, it was not. Therefore, I believe that this analysis is beyond Ellery’s thought process and should be regarded as later speculations by others.

The issue of “false clues” and “manipulation” that repeatedly appear in Ellery Queen’s later works has been discussed extensively by previous scholars. One can refer to the Douban diary entry titled “An Investigation of the Logical Problem of a False Clue” by z55250825(https://www.douban.com/note/825304889). I would like to emphasize that the logic of jumping back and forth between two conclusions, abandoning conclusion q if it is discovered that it might be induced by the culprit, and obtaining conclusion -q, is only applicable to Ellery Queen’s works. If this logic is believed to be universally valid, it would lead to significant misunderstandings when reading Agatha Christie’s works. Misdirection may not always be the work of the culprit, and even if it is, it cannot be concluded that q is wrong or that -q is correct.

If one wants to avoid these problems, the most feasible approach is as mentioned earlier, by introducing strong axioms or establishing specific settings. If that is not feasible, one can introduce more complex settings.

However, Ellery Queen has actually pointed out another path, although it is too obvious for many to see. That is, to let the detective fail once.

If the detective smoothly and directly deduces the truth of the case without any obstacles, the novel would end, and readers would easily doubt the correctness of that conclusion, leading to the problem of “false clues.”

If the detective initially arrives at an incorrect conclusion, then undergoes a reversal and a face-off, and finally fails, accepting the true solution, readers will have more trust in the “true solution.” They would consider the issue of false clues before the true solution, while potentially overlooking whether there is another layer after the true solution.

The hard-earned “solution,” achieved through great effort and even failures, appears more credible. This can be compared to a common trick in detective novels: if something/character appears out of nowhere, you would be highly suspicious of it. However, once the author assigns it a certain meaning, you would stop considering whether it has any other purpose. This trick frequently appears in Seiichiro Oyama’s short stories, and I believe you can understand my point without further elaboration.

In fact, in order to make the final solution appear more reliable, the detective can have multiple misinterpretations, not just once or twice.

Therefore, the later works of Ellery Queen repeatedly follow the pattern of “misinterpretation → reversal → distress → true solution.” This technique is not meaningless but serves to enhance the credibility of the true solution.

In the 1940s, Dannay wrote a letter to Stribling, in which he also provided some explanations:

“Let’s dig into the story. . . . First, let me say that I have no objection per se to a detective failing. In fact, I like the idea: it’s refreshing, and the bigger the detective, the more refreshing his failure to solve a case. But I don’t think that mere failure for failure’s sake is enough. The failure should be an integral plot-idea of the story; there should be a reason for the failure, an interesting reason—more, a clever reason.”

(Quoted from Arthur Vidro’s research article “The Return of Poggioli: T.S. Stribling’s Sleuth Given a New Home in EQMM.”)

In my understanding, this reason is to make the ending more convincing. The actions are taken to prove the rationality of the final solution.

So, for this kind of behavior, I can only describe it as going through hell, being battered and bruised, and then climbing up to heaven along the escalator.

Moreover, Ellery Queen would even push the final outcome to an irretrievable point where both the detective and the culprit find themselves in a deadlock. Both sides face a situation where there is no way out: the detective deduces the identity of the criminal, but he has no evidence, only inferences; the criminal knows that the detective has discovered the truth, but he cannot harm the detective. This approach actually weakens the importance of the truth: if even the final direction of the story cannot be determined, how important is the truth of the case?

Here, there are two factions divided by their perception of the truth: those who believe it cannot be determined and those who still consider it important.

I speculate that there is someone who pondered over how to handle the truth, realizing this point. In his novels, he repeated the aforementioned pattern and overturned the original solution at the end of the story, presenting a completely new “truth.” However, he did not strengthen the authority of the final solution; instead, he diminished its credibility, allowing the false solution to stand alongside it.

Only one person can reach the pinnacle of the work. Who will occupy that position? The detective, the culprit, or someone else? It may be a fallacy, but I believe that the problem in Ellery Queen’s later works, if expressed in a different way, is essentially “how to ensure that the detective reaches the highest point.”

Can a detective become a god?

From the title of the initial work, “MESSIAH,” it can be seen that several “god” figures will appear in the story. However, unlike the later works, my initial idea was simply “the Prime Mover = god,” similar to the model of “Aristotle = Thomas Aquinas.” In other words, only the person who draws the final curtain can qualify as the “god” or the “Prime Mover.”

It is a race to overcome the obstacle of obtaining the sole absolute position. When I reviewed “Wings in the Dark,” I further emphasized this aspect. And <……> was fortunate enough to obtain this position, but it actually deviated from my original intention.

I say this because if this is a world where the authenticity of clues cannot be fully determined, then the absolute status of the god will naturally be subject to constant reversal, that is, the so-called “infinite loop staircase.”

In the work, <……> seems to have successfully wrapped up the case, but <……> is only a “temporary” god. The world believes it is <……> who solved the case, while the readers believe it is <……>. If the two are not equivalent, it would be troublesome… Therefore, in the final chapter, although <……> has a conversation with the real culprit, the subject of the conversation is not explicitly stated except in one instance. And that one instance is narrated from a first-person perspective, indicating that it is <……>’s own perspective. By not explicitly stating the subject, it also implies that <……> doesn’t necessarily agree with it.

Of course, I will not reveal who this person is in the future. Because even if I did, it wouldn’t be very meaningful (I once published an article within the company titled “The Infinite Loop Staircase,” as I expected, it was criticized as unnecessary). And if the upper layer is confirmed, it becomes another “temporary” god, so I have to imply once again that there is another layer above.

Since I cannot introduce the “absolute” element into a story that escalates progressively, I can only handle it through implications. That was my conclusion at that time (and perhaps still is now?).

The way Yukito Ayatsuji handled the ending of “The Wings of the Dark” also reminded me of a certain work by Carr. This kind of treatment allows the truth to be considered important or unimportant. The reason for handling it this way is that it is “impossible to introduce the ‘absolute’ element into a story that escalates progressively.” In other words, “gods don’t make mistakes, a god’s strike always hits, and the god can solve the case as soon as it occurs, so the god can only descend at the end.”

Perhaps this understanding may not satisfy readers. Should we preserve the god or should we slay the god? It’s quite distressing, so since there is no way forward, it’s better to leave it blank, leaving behind a dilemma.

Why can’t we consider the truth as unimportant? Obviously, regardless of how it is defined, detective fiction must have a mystery and a solution. Without a solution, it cannot be considered detective fiction. The truth can only be “relatively unimportant” but not non-existent, so such a categorization doesn’t exist. But how “relatively” important is it? That cannot be determined, so “relatively unimportant” falls under the broader category of “inability to determine importance.” If we insist, in my opinion, the reason for the inability to determine is that the solution provided by the detective can be strong or weak.

On the other hand, for those who still believe the truth is important, the premise of creating a dilemma where both the detective and the culprit are in a predicament is simply not possible. If we cannot determine who the culprit is, the story must continue. Once we can confirm the identity of the culprit, we can wrap up the remaining issues. From this perspective, Ellery Queen is not as decisive as Philo Vance.

The original episodes 857-858 of “Detective Conan” titled “The Shifting Mystery of Beika City” attempted to challenge this dilemma. It is considered one of the best cases in the later stages of “Detective Conan.” Allow me to provide a brief summary.

In the final stages of the case, Conan deduces the entire criminal process and identifies the culprit as X. The culprit asks, “Conan, let’s assume your deduction is correct, but even if the deduction itself makes sense, the mystery remains unsolved.” This is because X lacks a motive for killing the victim.

At this moment, Conan looks up and faces the culprit, stating, “The clue to solving the mystery is what X left behind. It is a golden rule of detective fiction to hand over all the necessary clues for solving the puzzle to the investigating party.” So X left behind the key clues necessary for solving the mystery. It is these clues that fill in the missing motive.

After listening, the culprit exclaims, “You really managed to solve this mystery.” Conan continues, “These are all circumstantial evidence; it’s just my deduction.”

Next, the culprit smiles and without hesitation says, “Nonsense! Once the mystery is solved, it’s over. A pure detective story doesn’t need those mundane elements like physical evidence.”

Everything comes to a halt.

Immediately after, the culprit confesses and turns themselves in to the police.

In the handling of the case by scriptwriter Nobuo Ogizawa, he also considered the scenario where the culprit doesn’t confess, so he included a scene where Conan secretly records the conversation on his phone.

What he expresses is that a detective story only needs to surprise the audience by revealing the truth, and while evidence is certainly important, it holds no significance in the face of a fully constructed logical chain.

The approaches taken by the creators are full of talent and ingenuity, but I feel there is still a sense of regret as no one has been able to solve the problems set by the gods perfectly.

So far, let’s summarize the line of thought.

If we agree that detective fiction is a game, a battle of wits relying solely on intellect, then once the truth is revealed, everything comes to an end. Chaotic scenes, impossible puzzles, and elaborate schemes all become nothingness, and the world returns to its calm state, just as it was before.

If we are willing to view it from the perspective of a game, there is a way to resolve the confrontation between the culprit and the detective: the losing party gives up futile struggles, and the culprit surrenders; if the detective loses… well, the detective must exit the stage and make room for someone else who can uncover the truth. What the author needs to do is to provide a final solution that stands up to scrutiny.

However, if the culprit simply fails and surrenders, it can become formulaic, and readers might ask questions like “Why?” or “This is too unrealistic.” If the culprit is caught through a plot device or the detective resorting to dramatic methods, readers might question, “Is the truth really like this?”

We need a new form that makes this game more plausible.

Excursion Into Time

In the previous discussion, it was mentioned that detective novels can be seen as a game. In the following paragraphs, this perspective will be further explored.

In “The Player on the Other Side,” there are two chess matches being played simultaneously: one between Y and Walter, and another between Y and Ellery. In this context, Ellery seems to realize that detective novels depict a contest between the detective and the culprit, with the detective employing reasoning and the culprit resorting to tricks and schemes.

From a chess perspective, if both sides are evenly matched, there is a high probability of reaching a balanced and drawn outcome. In detective novels, this would be reflected in both the detective and the culprit being in a deadlock, unable to gain the upper hand.

However, this intellectual battle bears similarity to a real game of chess, where the detective possesses the advantage of making the first move. This advantage is significant, and even if both sides make optimal moves, the detective can still outwit the culprit due to the initial advantage. (In various card games, there is often an inherent advantage in going first unless there are compensatory rules or special provisions.)

Indeed, there are game modes where the second player is guaranteed to win. Regardless of the specific mode, after strict regulations, one can apply Zermelo’s theorem: in a two-player finite game where both players have complete information and luck is not a factor, either the first or second player will have a winning/draw-guaranteed strategy. However, for now, let’s not delve into this theorem. Let’s assume that in the contest between the detective and the culprit, the detective always moves first, but it is uncertain if the second player is guaranteed to lose.

According to Locard’s exchange principle, there is always a physical exchange of evidence between the suspect, the crime scene, or the victim. This means that once a crime occurs, there must be clues pointing to the culprit. Therefore, the initial situation between the detective and the culprit is not a balanced one. The detective has the advantage, and the culprit is forced to respond. The detective strikes by exposing loopholes, and the culprit must defend and strategize for a counterattack.

The conclusion is that all the strategies of the culprit revolve around the clues that point to themselves. This aligns with what was advocated in the first phase: human actions have a purpose, and we can reason out both the purpose and the person behind it.

Can the culprit act idly? Is it possible for them to leave unrelated clues? Obviously, the reason for leaving unrelated clues is to confuse the true clues. Can they deliberately engage in meaningless actions? Similarly, when the detective starts contemplating whether a clue or behavior is relevant to the case, it is precisely when the culprit considers if it will lead back to themselves. Therefore, I believe the above conclusion is correct and reliable.

Unfortunately, detective novels cannot be as orderly as a game of chess. It is difficult to say that the detective can checkmate the culprit based on a single move of reasoning. Even if the detective truly corners the culprit through their deductions, forcing them to surrender, as mentioned earlier, readers may not fully accept it. They might question, “What? The culprit was convinced and confessed due to the detective’s reasoning. Does that align with reality?”

It can be said that it complies with the rules of the game but goes against common sense. If we assume that the detective must apprehend the real culprit, then when they have no evidence for an arrest, they must still take action and not remain idle. However, unfortunately, when Ellery encounters such a situation, he restricts himself. He confronts the suspect face-to-face, similar to Poirot, but he cannot pass judgment like Sherlock Holmes, punish the culprit like Gideon Fell, or… Although Ellery has had a few extremely unconventional actions, in most cases, he is quite restrained. This conforms to the mindset of repeated failures in battles, and this self-disciplined behavior turns what should be a satisfactory resolution into shattered tragedies.

If we acknowledge that the detective is only responsible for reasoning and not for apprehending the culprit, there is another approach that is more commonly seen and well-known in games, specifically “Ace Attorney” and its courtroom trial mode.

Both the prosecution and the defense strive to find the real culprit, and the detective’s role is to act as a witness, unraveling the deception or reconstructing the truth.

This is precisely what Queen attempts in “The Tragedy of X,” “Halfway House,” and “Calamity Town.”

Let’s take it a step further. What if both the prosecution and the defense were exceptionally brilliant detectives? Let’s set the premise that neither side is the culprit. In this scenario, they have no burden or advantage. They simply have differing opinions and choose their preferred suspect to accuse, while the real culprit is present in the courtroom. At this moment, Chesterton’s famous quote needs to be used in reverse: the detectives are creative artists, and the culprit is merely a critic scoring their deductions.

In this case, both sides have equal information, and there is no element of luck in winning or losing. Can we discuss strategies that guarantee victory or an unbeatable strategy? Perhaps not, because while the information is equal, it is not complete: the problem of resolving false clues must be addressed, as the logical game cannot continue otherwise. Therefore, I believe that Queen’s later issues must be resolved someday.

However, this is not the focus of this article. The discussion about new forms of courtroom reasoning should be left for future research and discussion.

As for why Ellery never adopted a similar format, I speculate that it is because Queen is too determined to ensure that Ellery ultimately arrives at the correct truth. He can make mistakes, one or two times, but in the end, he must be right. So, regardless of the case, the control lies in his hands. He is the protagonist, and the only opponent he can face is the culprit.

Can we analyze “The Glass Village,” “Inspector Queen’s Own Case,” “The House of Brass,” and “Cop Out” as case studies?

“Inspector Queen’s Own Case” is not suitable since Richard Queen happens to stumble upon the truth after repeated failures. This approach is no different from his son’s stories.

“The House of Brass” is also not suitable. Ellery only appears in the final chapter, and the reasoning led by Richard in the earlier parts is incorrect. Ellery’s role is to correct Richard’s mistakes.

“Cop Out” involves a battle of wits, but it still follows the pattern of the police apprehending a fugitive, similar to stories featuring Lincoln Rhyme. The culprit leaves too many clues in the police’s home, essentially playing their hand openly.

The above three works do not align with our discussion of a fair competition between the two sides.

What about “The Glass Village”? I believe it is suitable. Before analyzing it, let me provide some background on the book.

“The Glass Village” is a commemorative work for the 25th anniversary of Ellery Queen’s debut and was selected by the MWA as one of the best detective stories of the year. Ellery has had two commemorative works, and neither of them features the appearance of Ellery himself.

This story was adapted into a television drama by NBC on September 26, 1958, where Ellery made an appearance. In January 1961, a radio drama adaptation based on the work was broadcast on Dutch radio. There is some evidence suggesting that “The Glass Village” was originally intended to be a Wrightsville story featuring Ellery but was later changed to Johnny and Shinn Corners, with Ellery’s appearance in the TV series serving as supporting evidence. The omission of Wrightsville or the use of two different settings may have two possible explanations. Firstly, the residents of Shinn Corners may have been portrayed as more simplistic and narrow-minded, which would not align with the larger community background of Wrightsville. Secondly, Queen might have had a fondness for the residents of Wrightsville, and it may not have been appropriate to depict them as a mob, as transforming good citizens into McCarthyism-style characters would be inappropriate.

Then, I have a conjecture that Queen perhaps believed that Ellery was powerless in the face of these villagers.

So, the conclusion is that Queen, in order to write this story, may have even allowed Ellery not to appear. To create this story, he abandoned the unsuitable Wrightsville and created a fictional village like Shinn Corners, which was only used this one time. Clearly, there is something he wanted to express or pursue in this book.

It is worth mentioning that “Terror Town,” included in the “The Misadventures of Ellery Queen” collection, also features a New England village called Northfield, which only appeared once in the canon. This statement is not absolute and is limited to novels.

Of course, there is an epilogue to this village. Shinn Corners later became a recurring location in Edward Hoch’s “Sam Hawthorne,” series but we do not know if Queen had any instructions for Hoch regarding this. In “The Last Woman in His Life,” it is explicitly mentioned that Johnny Benedict’s secluded residence occupies two hundred acres, located between Wrightsville and Shinn Corners (note: this Johnny is not the same as the one mentioned later in The Glass Village). The book describes:

From the way Benedict had talked Ellery expected a dilettante twenty or thirty acres. They found instead a two-hundred-acre spread of timber, water, and uncut pasture halfway between Wrightsville and Shinn Corners, in a farmed-out section of the valley where it began to creep up into the northwestern hills. The property was barred off by tall steel fencing and posted against hunting, fishing, and trespassing generally, in large and threatening signs bolted to the fence.

In “The Glass Village,” the entire story, from the courtroom proceedings to the final truth, bears some similarities to “Ace Attorney,” but it is concealed more deeply and there is not much mention of leaks. The fourth chapter’s courtroom debate is a fair contest, although some readers who have read this work may have objections to the concept of “fairness.” The debate in this chapter is to prove Josef Kowalczyk’s innocence, and in that regard, the contest between the prosecution and defense is fair and just. Once the winner is determined, the matter can be resolved, and Johnny achieves that.

In Chapter 3 of “Halfway House,” Bill is unable to successfully clear Lucy’s suspicion in court. He presents some doubts, such as illogical actions on Lucy’s part if she were the murderer, which would be too foolish to believe. However, the prosecution argues that in real-life crimes, suspects cannot be as perfect as fictional criminals, and some inconsistencies can be understood. Ultimately, due to the fingerprints Lucy left on the murder weapon, the jury reaches a guilty verdict. As we can see, the defense did not have enough evidence and reasoning to prove the innocence of the suspect, so they were at a disadvantage in the contest. In “The Glass Village,” it is the opposite. The facts that are ultimately revealed can already prove the innocence of the tramp, and the guilty verdict is only due to the prejudice of the jury. Based on the actual situation in the courtroom, I believe it is possible to reach the conclusion of the suspect’s innocence. “The Glass Village” does something that previous Queen novels did not. Ellery always needed further confirmation or various methods to force the real culprit to reveal themselves, and it was only when the real culprit was revealed that the suspect was declared innocent. Therefore, I believe the reason Queen liked “The Glass Village” is that it relies solely on a fair confrontation, where once the winner is determined, the suspect’s charges are cleared without further explanation. Of course, this is a personal opinion and there is no evidence to prove this.

In summary, the situation in “Halfway House” is that the defense needs to prove that there are other possibilities besides the prosecution’s evidence, while in “The Glass Village,” the defense proves that the prosecution’s fundamental arguments are incorrect. The dynamics of offense and defense are different in each case.

From the discussion of “Halfway House,” we can draw another conclusion: what is logically valid may not necessarily exist in reality, and what is logically invalid may exist in reality. This statement aligns with what Drury Lane said in “The Tragedy of Y,” “[Logic is] something utterly different, so utterly different that it transcends the bounds of common sense”. Furthermore, let’s analyze from Queen’s perspective why he arranged the plot of the defense’s failure in the third chapter. Could the story be modified so that Ellery had already collected all the clues before the trial and pointed out the real culprit through reasoning and evidence in court? My personal understanding is that although Queen is capable of and could have planned it that way, he would not have done so. The problem lies in the prosecution’s arguments mentioned earlier. The prosecution believes that although the defense’s doubts are reasonable, the defendant’s suspicion cannot be cleared simply because the logical points exist. The defense cannot prove the defendant’s innocence. Therefore, with the presence of the defendant’s fingerprints on the murder weapon and the defendant being at the crime scene, the defendant remains the prime suspect. Queen needs this prosecution’s argument to initially appear strong and then be refuted in the end to demonstrate the power of his logic. During this period, he still believes in the omnipotence of logic. As described in the challenge of this work, “But we have a sound defense. Guessing isn’t fair.”. So, from the perspective of a straightforward victory or defeat, one could say that “Halfway House” is not as pure as “The Glass Village.”

However, is this statement correct? Not necessarily.

Through reading Queen’s detective novels, I have learned a lesson: the path of reasoning is always winding, and the reasoner can only progress in a circuitous manner; they cannot reach the destination in a single step. It is normal for reasoning to make mistakes in this process. When proposing a deduction, it should not only be supported by evidence and arguments but also consider whether it is the only possibility and whether other deductions could be valid. The same applies to reasoning discussions; they should not be the only perspective, and various viewpoints can emerge during the process of argumentation. What we need to do is seek common ground while respecting differences.